Where does the boundary lie between animal and human? Can the transformation of human into animal be positive as opposed to the frightening werewolves of horror stories?

Paula Rego’s ‘Dog woman’ was inspired by a story that a friend had written for her. She depicts women behaving like dogs in monumental poses, including howling at the moon, grooming and sleeping on her owners coat. Her use of pastels connects her work to the raw physicality of Degas women, relishing the resistance they give against the paper surface and eliminating the distance from the work that comes with a brush. The work challenges accepted feminine behaviour and conventions of representation. She explains; “To be a dog woman is not necessarily to be downtrodden; that has very little to do with it,” She explained, “In these pictures every woman’s a dog woman, not downtrodden, but powerful. To be bestial is good. It’s physical. Eating, snarling, all activities to do with sensation are positive. To picture a woman as a dog is utterly believable.“ A dog is a unique animal in its juxtaposition of the domestic and the wild, and parallels can be drawn with the lives of women – they learn behaviours from those around them but maintain a strong bodily independence. Casting a woman as a dog emphasises this physical side of the body. Rego says that the series of works is about the love she had for her husband Victor Wiling – having become the obedient wife herself, she explains how female students at the Slade were groomed to become the muse or empathetic partner of a male artist, which perhaps has something in common with the relationship between dog and owner. Although she used a model named Lila, with whom she had a very close relationship, she says that her model stands in for herself and the scenes depicted are based on personal stories. She first instructed Lila to ‘crouch there and growl’ and the resulting image gave way to a recurring theme.

Paula Rego, Dog Woman, 1994.

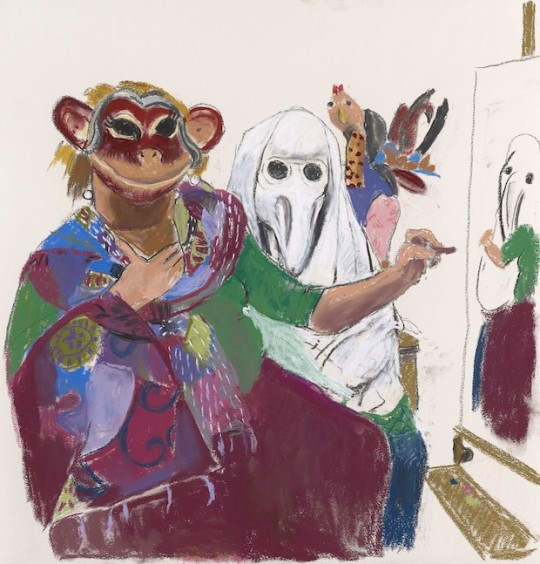

Eileen Cooper’s work most commonly features female nudes alongside animals, and there is an interesting lack of differentiation between the two. Both are painted with expressive and primitive qualities using line, so that animal approaches human and human approaches animal. The work encapsulates universal themes such as the dynamics of family relationships, female sexuality, fertility, motherhood, creativity and life and death. Like Paula Rego, Cooper paints women in unconventional poses, defying expectations of feminine grace for an animalistic physicality – A woman crouches naked on her studio floor to paint, her shoes cast aside as if to give way to her inner animal – the animalistic side of creativity. It could be said that these are women who are truly naked as opposed to performing ‘the nude’ as an art form. Imagination plays a large role in the conception of Cooper’s images - ‘I love the idea that the studio is the kind of place you might get a tiger walking through.’ Tigers are a recurring feature of her painting – As a woman stands on her head in a simplistic landscape, a tiger floats above her as though it were her spirit animal.

Eileen Cooper, Law of the Jungle, 1989.

Eileen Cooper, Law of the Jungle, 1989.