The Madonna and child, Holy trinity, Annunciation and Nativity are all scenes you might find on the walls of a church. But the iconography of religious artwork has become so ingrained that we see it being borrowed in works that are not intended for an explicitly religious purpose. Many non-religious artists refer back to the bible stories they were taught as a child in school as a source for creative imagination.

‘Take your son, Sir’ (1851-6) is a painting by Ford Maddox Brown. It shows his second wife with their new born son. The seated symmetrical pose recalls traditional Madonna and child paintings. The circular mirror behind her head stands in for the traditional gold halo, whilst the starry wallpaper suggests the heavens. Despite this, the use of the artist’s own family as models and the domestic setting indicate that this is not simply a rendering of Mary and her infant Jesus, but a scene from contemporary life. The viewer is implicated as father, reflected in the mirror behind. The mother’s strained expression suggests that this is not a conventional celebration of marriage and motherhood. This may be explained by the death of their son at ten months, which is likely why the painting remains unfinished. Some interpret it as a more confrontational image, in which an abandoned mistress presents her baby to its father. This would have been a popular subject in Victorian pre-Raphaelite painting which valued a moral message. The painting displays a deliberate paradox between new life and death.

Ford Maddox Brown, Take your son, Sir, 1851-6.

‘Madonna’ is the title given to several paintings by Edvard Munch, depicting a half-length female nude figure with flowing black hair. Based on the title and red halo it was possibly intended to represent the Virgin Mary. She embodies some of the conventional aspects of the Annunciation scene, in her quiet and calm confidence, her closed eyes expressing modesty and her body twisting away from the light. However these references are disputed as Munch was not known to be a Christian. He may be drawing upon an affinity to Mary to emphasise the beauty and perfection he saw in his model, and as an expression of worship of her as an alternative ideal of womanhood. The flowing black hair, pale skin, red lips and nudity give her a vampiric appearance and suggest she may represent the femme fatale - the strong woman who reduced man to subjection through seduction. Her dual gesture of surrender and captivity in her arms behind her back serve to mitigate this assertion of female power. These undertones of sensuality and death invert the portrayal of the virgin mother.

Edvard Munch, Madonna, 1895.

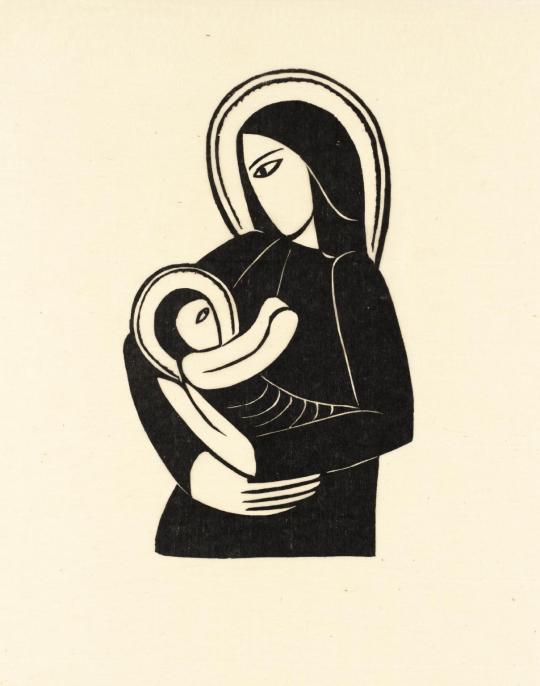

As a devout Christian, Eric Gill often used religious imagery in his work. His life was marked by a tortuous religious exploration and he converted to Catholicism in 1913. He made many compositions on the subject of the mother and child, in both sculpture and wood engraving, but with a stylised modern twist. He was part of a new artistic generation that heralded the development of modern British sculpture. His Madonna and Child of 1919 is typical of the erotic religiosity that Gill employed to add a new and compelling dimension to the traditional subject of Madonna and Child. The figures are simplified and geometric, and the profile of their faces is represented by a single eye. Despite this modern simplification, the halos and the curved geometry of the figures recall Byzantine icon painting, used as an object of veneration in Orthodox churches and private homes in the Eastern Roman Empire. It placed an emphasis on symbolism over naturalism, and conformed to strict canons of representation in order to manifest the unique presence of the figure depicted.

Eric Gill, Madonna and Child, 1919