Rodin’s sculptures were carved in a large, productive workshop, in collaboration with many studio assistants. Out of the strenuous labour and noise of the studio environment emerged a collection of surprisingly sensitive, quiet sculptures of the human figure. One of these studio assistants was the young Camille Claudel, also a sculptress in her own right. Subjects which may be considered ugly to some become beautiful in the eyes of these two artists, due to an expressiveness and strength of character.

Rodin’s Eve remains unfinished because his model, who was pregnant, could no longer hold the pose. Almost twenty years had passed before he felt bold enough to exhibit his incomplete or fragmented works. The rough surface of the skin, the lack of detail and the trace of the metal armature still visible on the right foot all attest to the fact that this was a work still in progress. The modesty of her gesture and the shame which it suggests collide with the sensuality of her body. She takes up a closed variation of a contrapposto pose. Suffering is conveyed by the twist of her body and anguish in her face. Rather than the originator of sin, she appears to represent the frailty of the human condition.

Rodin, Eve, 1881

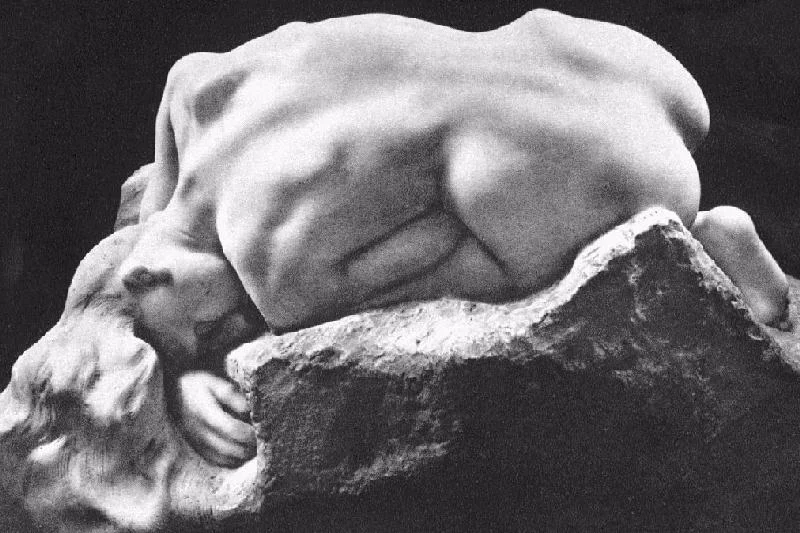

In Greek mythology, the Danaïds were punished for killing their husbands on their wedding night by being made to fill a bottomless barrel with water. Rather than representing the Danaïd in the act of filling the barrel, as in conventional iconography, Rodin strips the subject down to her inner despair as she realizes the pointlessness and absurdity of her task. She rests her head on her arm in exhaustion, ‘like a huge sob’. Rodin constructed a feminine landscape from the curve of her back and neck, culminating in the flow of her hair into the water from her overturned vase. But for all her soft curves and suffering we know she is not a fragile or helpless woman – she stabbed her husband after all. The jagged surface of the rock forms a contrast against her smooth skin. Whilst her hair falls forward to reveal her neck in a soft gesture, the bridge of her back remains strong like a shield for the rest of her body. There is a muscularity in the modelling of her shoulders. Some say that the model was Rodin’s assistant and lover, the sculptress Camille Claudel, whereas others suggest the pose was inspired by a fatigued studio model in rest.

Rodin, Danaid, 1889

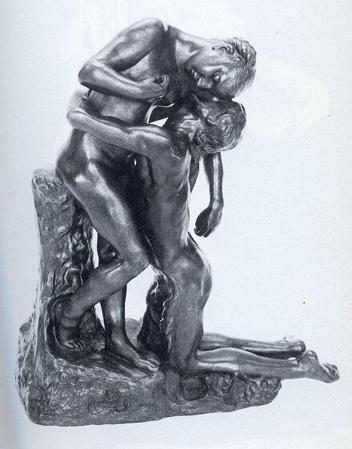

Possibly most representative of strength and fragility was the work of Camille Claudel – a strong woman working in the male dominated medium of stone, worn to fragility by the hardships she suffered as a result of her gender. In Rodin’s studio she was often mistaken for a model as it was unusual for a woman to be present in any other capacity. She worked as his assistant as well as creating her own original works, leading her skilful modelling to be often accredited to him. Although she has been characterised as a tragic heroine and victim in popular adaptations of her life story, she was an artist whose work reached critical acclaim independent of her biography. L’Abandon was inspired by an Indian play about Sakuntala’s reunion with her husband after a long separation caused by a magic spell. It morphed into a personal response to Vertumnus and Pomona in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. The female figure stands over the kneeling male. Pomona was the nourishing goddess of fruits – she is supported by strong and muscular legs. Vertumnus clasps her in an arduous embrace, straining his neck to reach her. She appears to give in to his attentions despite efforts to resist. One of her arms hangs limply at his side, the other protects her heart. Although she is depicted in the process of submitting, she is eternally suspended between independence and commitment. The arrangement speaks of a mutual dependence. Rodin’s refusal to give up his wife for Claudel and being forced to live in his shadow drove her to paranoia. Her career was tragically brought to a premature end and she was committed to a mental asylum for the last 30 years of her life.

Camille Claudel, Vertumnus and Pomona / L’Abandon, 1886