Masks have made an appearance in various artistic movements. They are full of ambiguity – is it a figment of the artists imagination or is the sitter wearing a mask? They were a trope of decadence, a late 19th century artistic movement characterised by excess and artificiality, a critique of the ‘sickness’ of society. Decadent writer Arthur Breisky wrote ‘isn’t it necessary to believe a beautiful mask more than reality’

Aubrey Beardsley, The Scarlet Pastorale, 1896.

Belgian painter James Ensor’s work is known for groups of masked figures, reflecting the carnival traditions of Belgium and the Netherlands. He worked in the attic of his mother’s souvenir shop surrounded by masks and costumes from the stock. Whilst the mask is often worn to conceal identity, for Ensor it had a much greater potential. He exploited its anonymity to transform reality into the strange and unsettling. Ensor’s distorted masks reveal the true character of their wearer as malicious and superficial – satirising public figures and challenging religion and politics. The crowd depicted in ‘The Entry of Christ into Brussels’ is a combination of bourgeoisie, clergy, and the military. The mask may be a metaphor for the solitude of the individual in the increasing masses of society. They mingle with clowns and skulls, both dehumanised and threatening. Garish colours give the scene an otherworldliness and bring it into the realm of symbolism.

James Ensor, The Entry of Christ into Brussels, 1889

Paula Rego often works with masks, paper mache dolls and stuffed toy animals, using them to tell stories in her paintings. The use of props such as masks reveals the constructed artificiality of her imaginative world, suggesting it is in fact closer to reality than we think. This is demonstrated by her painting ‘War’, which features several figures wearing rabbit masks. Rego says the work is a response to a photograph she saw in the Guardian of a screaming girl in a white dress running from an explosion in the Iraq War, while a woman and a baby stand on the spot behind her. Rego explained, ‘I thought I would do a picture about these children getting hurt, but I turned them into rabbits’ heads, like masks. It’s very difficult to do it with humans, it doesn’t get the same kind of feel at all. It seemed more real to transform them into creatures’. The masks may give the scene more impact by making it relatable, as the figures could stand for anyone. Art historian Philippe Dagen compared ‘War’ to a child’s nightmare generated by books or films, which ‘instantly perverts its previously happy and warm world’. The resemblance of the masks to children’s toys - made grotesque -enhance their nightmarish qualities.

Paula Rego, War, 2003

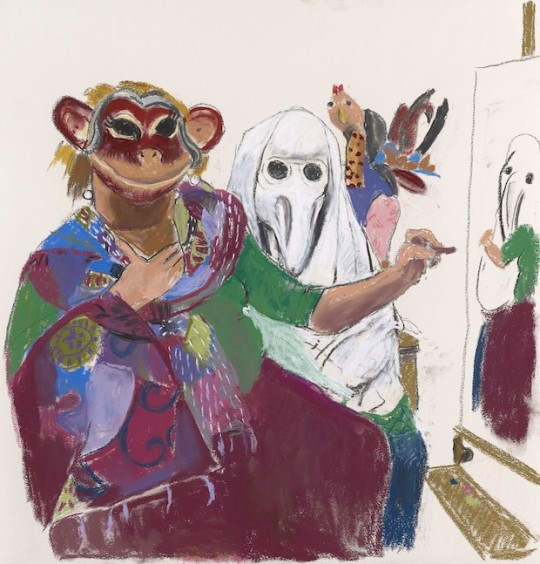

Paula Rego also painted self portraits whilst wearing a mask. It is important that her portraits are completed from observation, using props, rather than being from imagination. This creates a confusion between reality and artifice, adding to their strangeness. It may be a comment on the inescapable artifice of art.

(Paula Rego painting herself wearing a mask)